Lead

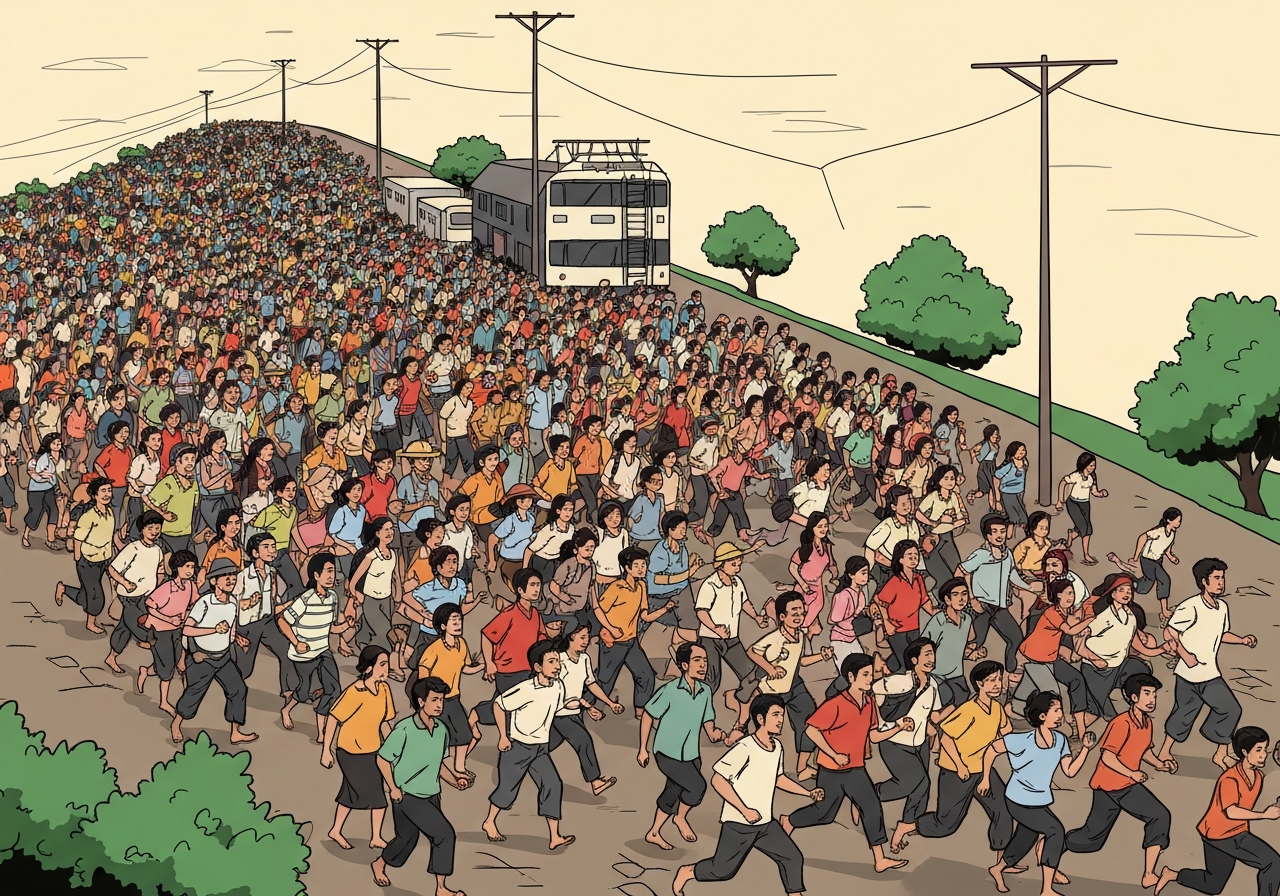

In early 2026 thousands of people began leaving so-called ‘scam compounds’ in Cambodia, many arriving in Phnom Penh with little more than the clothes they wore. Over recent weeks shelters and civil-society rescuers have been overwhelmed as large numbers of foreign workers are released or escape, creating visible humanitarian strain on city streets. One Caritas-run shelter that previously received U.S. funding now operates with a fraction of its former budget and staff and has turned away more than 300 people. The surge follows international pressure and government action against cyberfraud operations.

Key Takeaways

- More than 300 people have reportedly been turned away by the principal Caritas shelter as it struggles with reduced funding and staff.

- The shelter housed about 150 people last week, with many sleeping in a common room and lacking pillows and blankets.

- Cambodia’s government reported deporting 1,620 foreign nationals linked to scam operations in January 2026.

- The U.N. OHCHR estimated up to 100,000 workers were employed in scam operations in the region in 2023.

- Caritas had expected $1.4 million in USAID funding from Sept. 2023 into early 2026; that pipeline ended after U.S. foreign assistance was suspended in early 2025.

- Rescuers have documented dozens to hundreds of newly released individuals; one rescuer listed 223 people seeking help, mainly from Uganda and Kenya.

- Some return to the compounds or accept collective hotel rooms when no durable return or resettlement options exist.

Background

Online fraud operations using closed compounds have proliferated across Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar in recent years. Those facilities commonly run multilingual scripts, use foam-lined phone booths for soundproofing and have even built mock police checkpoints to intimidate victims or lend false legitimacy to operations. International agencies and rights groups estimate the industry employed large numbers of mostly foreign nationals by 2023, creating an embedded commercial ecosystem.

In response to mounting diplomatic pressure from nations including South Korea, the United States and China, Cambodia’s leadership publicly prioritized cracking down on cyberfraud in late 2025 and early 2026. That response included detentions and deportations but also appears to have triggered mass releases from many compounds. At the same time, funding and operating space for independent responders in Cambodia have narrowed amid a more constrained civic environment.

Main Event

The most immediate scene has been a steady outflow of people from compounds in northern border zones and urban hubs to Phnom Penh and other transit points. Verified social media footage and interviews collected by Amnesty International show groups exiting compounds in batches and arriving at shelters or gathering in public spaces. Many migrants report being pressured or coerced into scam labour, then abandoning the sites when enforcement or management changes occurred.

Caritas’ Phnom Penh shelter, previously supported by U.S.-linked funding partners, now operates with roughly one-third of its former staff and a sharply reduced budget. Staff and volunteers say intake capacity has fallen even as demand spikes. Shelter managers report having had to turn away hundreds of people and ration basic supplies such as food, pillows and blankets.

Individuals who arrive with little documentation face varied outcomes. Some are assisted by their embassies or escorted to repatriation flights; others cannot access consular help and either sleep on streets, pay bribes to avoid detention, or return to the compounds because they lack alternatives. Vulnerable individuals from conflict-affected or stateless communities, such as some Banyamulenge, cannot safely return home and thus remain stranded in-country.

Humanitarian actors on the ground describe a fragmented response: international organizations refer people to shelters that are full, independent rescuers absorb costs out of pocket, and government statements stress screening and assistance protocols while critics say implementation is uneven.

Analysis & Implications

The immediate humanitarian impact is clear: shelters that served specialized needs are now underresourced just as caseloads increase. Loss of U.S.-linked funding and cuts to agencies such as IOM have removed predictable support streams, forcing local actors into unsustainable short-term care or outright refusal to accept new arrivals. This heightens risk for returned or stranded individuals, including exposure to trafficking, detention, or recruitment back into illicit operations.

Politically, the crisis exposes tensions between international pressure to act on cyberfraud and the capacity or willingness of national institutions to provide protective services at scale. While the Cambodian government reports deportations and screening measures, activists argue that rapid releases without coordinated reintegration plans shift the burden to shelters and to receiving countries’ consular services.

Economically, the scam industry has generated informal revenues that touch local actors, complicating efforts to dismantle networks without parallel economic and legal remedies. For affected countries of origin, the sudden repatriation needs and consular demands may strain diplomatic resources, and inconsistent return pathways risk creating a secondary displacement problem across the region.

Comparison & Data

| Metric | Reported Figure |

|---|---|

| People sheltered at Caritas (last week) | ~150 |

| People turned away by shelter | +300 |

| Foreign nationals deported by Cambodia (Jan 2026) | 1,620 |

| Estimated workers in region (2023, UN OHCHR) | Up to 100,000 |

| Planned USAID support to shelter | $1.4 million (Sept 2023–early 2026) |

The table places recent operational pressures alongside regional estimates and funding lines. It underscores how a concentrated loss of funding and a sudden surge of released individuals can produce acute shelter shortages even when numbers seem modest relative to regional estimates.

Reactions & Quotes

Rights groups and rescuers emphasize a humanitarian emergency on the streets.

“Thousands of traumatized survivors are being left to fend for themselves with no state support,”

Montse Ferrer, Amnesty International (regional research director)

The Cambodian government rejects that characterization and highlights screening and assistance efforts.

“All individuals are screened to separate victims from perpetrators, with victims receiving protection, shelter, medical care, and assistance for safe return,”

Neth Pheaktra, Minister of Information, Royal Government of Cambodia

Local rescuers and shelter operators describe resource shortfalls and ad hoc responses.

“It’s become triage,”

Mark Taylor, counter-trafficking specialist (observer)

Unconfirmed

- Not all individual escape and transit narratives have been independently verified; some reports rely on survivor testimony and social-media material.

- Claims about the exact number of compound closures and mass releases nationwide remain fluid as verification lags behind rapid movements.

- Reports that officials uniformly ignored victims vary by locality; responses appear to differ between national statements and local practices.

Bottom Line

The exodus from scam compounds in Cambodia has produced an acute, visible humanitarian problem that outstrips the capacity of specialized shelters. Funding shortfalls, reduced international assistance, and a constrained civic space have left a narrow set of responders shouldering most of the burden while diplomatic channels and state systems attempt to manage law-enforcement priorities and consular flows.

Absent a coordinated regional response that combines funding for emergency care, clear consular procedures, and durable reintegration or protection pathways, many released individuals will remain vulnerable to detention, re-recruitment into illicit work, or long-term displacement. Monitoring, targeted support for front-line shelters, and transparent reporting on screening and assistance are immediate needs to prevent the situation from worsening.

Sources

- Associated Press (news report)

- Amnesty International (non-governmental organization reporting and interviews)

- UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (international organization estimates)

- International Organization for Migration (IOM) (UN agency; operations and briefings)

- USAID (former donor; funding context)