Lead

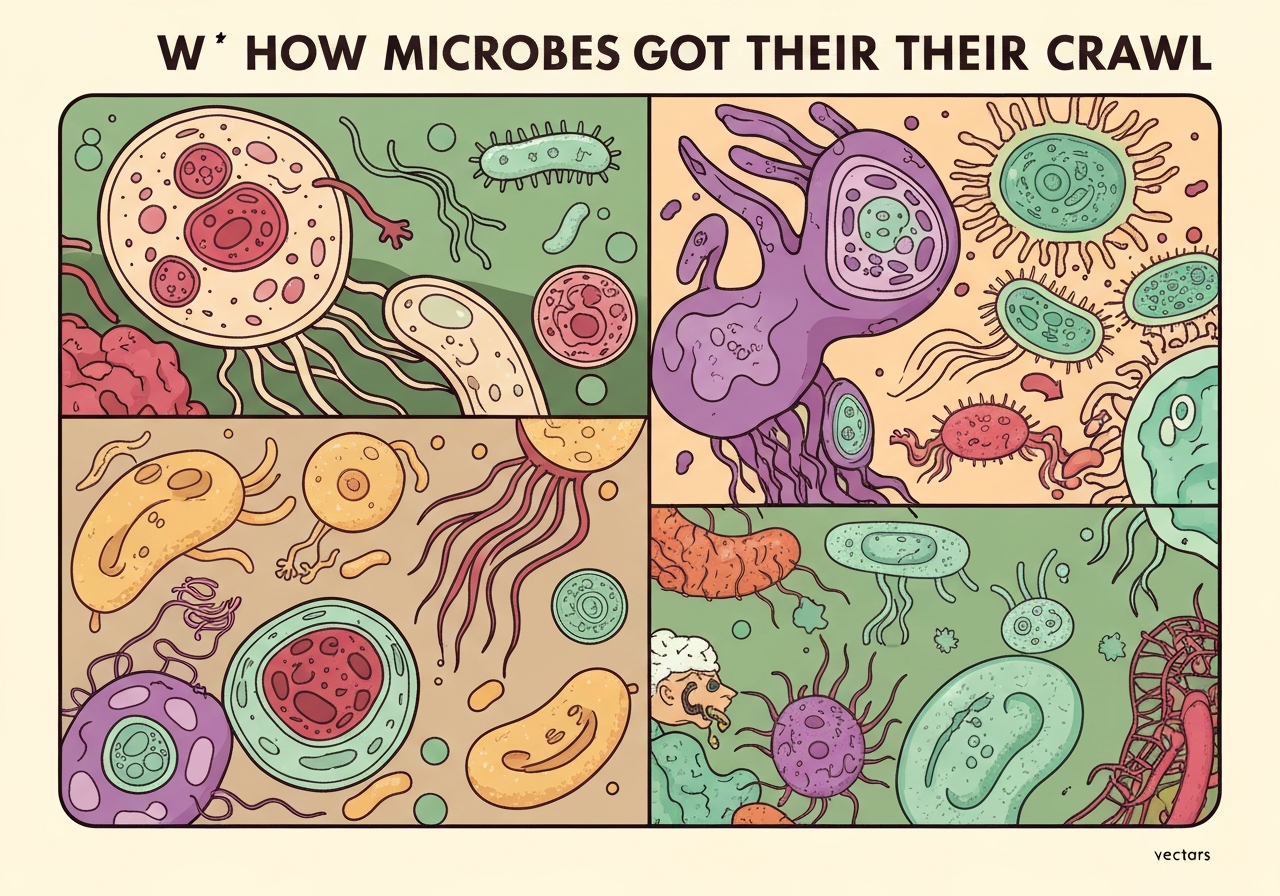

On Feb. 18, 2026, a cluster of new studies reported renewed evidence that rare microbes — including the recently imaged Lokiarchaeum ossiferum — occupy intermediate positions between the planet’s earliest single‑celled life and modern complex cells. Researchers say these transitional organisms, found in marine and terrestrial settings, illuminate steps that likely led to eukaryotes roughly two billion years ago. The work builds on long‑standing ideas about mitochondria originating from an engulfed oxygen‑using bacterium and asks what kind of host cell could have swallowed it. Together the findings tighten key links in a story that has puzzled biologists for decades.

Key Takeaways

- Researchers have identified rare, morphologically complex archaea such as Lokiarchaeum ossiferum that display internal filaments and membrane features once thought unique to eukaryotes.

- Prokaryotic life emerged more than 4.0 billion years ago; eukaryotes are estimated to have arisen between 2.5 and 2.0 billion years ago, narrowing the critical window for cellular innovation.

- Genetic analyses reinforce that mitochondria descend from an oxygen‑respiring bacterium, supporting an endosymbiosis event prior to—or concurrent with—other eukaryotic traits.

- New microscopy and sequencing techniques are revealing structural and molecular complexity in lineages previously classified as simple prokaryotes.

- Discoveries come from both ocean sediments and terrestrial samples, suggesting transitional forms were ecologically widespread though numerically rare.

- The findings reduce the explanatory gap but leave open the identity and biology of the precise host cell that incorporated the mitochondrial ancestor.

Background

The division between prokaryotes and eukaryotes is among biology’s most consequential. Prokaryotes — bacteria and archaea — lack membrane‑enclosed nuclei and organelles; their lineage dates back over four billion years. Eukaryotes, the group that includes animals, plants and fungi, possess intracellular compartments such as a nucleus and mitochondria and appear much later in Earth history, around two to 2.5 billion years ago.

For decades a central clue came from mitochondria themselves. Detailed genetic work in the 1990s showed mitochondria carry a small genome closely related to aerobic bacteria, implying an ancient symbiosis: an ancestor of eukaryotic cells incorporated a bacterium that later became the cell’s energy organelle. That insight explained how cells might have gained high‑efficiency metabolism, but it left unanswered what host cell could perform or permit an engulfment event and how other eukaryote features arose.

Main Event

Recent studies described in the Feb. 18, 2026 report document microbes with unexpectedly elaborate internal architecture. High‑resolution imaging of Lokiarchaeum ossiferum shows filamentous structures and membrane invaginations that resemble the cytoskeletal and trafficking apparatus of eukaryotic cells, albeit in simpler form. These morphological traits, paired with genomes that include genes once thought exclusive to eukaryotes, place such archaea on a putative evolutionary bridge.

Teams sampled sediments and rock matrices from diverse locales and combined electron microscopy with single‑cell genomics and metagenomics. The integrated approach allowed researchers to connect physical structures visible under the microscope with gene inventories from the same lineages. That dual evidence strengthens the interpretation that some archaeal groups had preadaptations for membrane remodeling and internal scaffolding before full eukaryotic complexity emerged.

Authors emphasize scarcity: these transitional organisms are not abundant in the environments sampled and are often detected only after targeted enrichment or deep sequencing. Multiple independent groups nevertheless recovered consistent patterns—particular gene families and partial cytoskeletal systems—across geographically separated sites, suggesting the features are evolutionarily conserved rather than artifacts of a single population.

The work also revisits the mitochondrial origin story. Comparative genomics continues to place mitochondria inside the tree of bacteria specialized for oxygen respiration, confirming an endosymbiotic event. The new twist is that host lineages already carried more sophisticated membrane and cytoskeletal machinery than previously appreciated, potentially facilitating engulfment and subsequent organelle integration.

Analysis & Implications

These findings narrow a conceptual gap in evolutionary biology: they supply plausible intermediate steps by which a membrane‑bound, compartmentalized cell could evolve from simpler ancestors. If archaea related to Lokiarchaeum possessed rudimentary scaffolding and membrane dynamics, they could have been predisposed to form stable associations with bacteria that later became mitochondria. That scenario reduces the need to posit improbable, one‑off innovations in a single lineage.

The implications extend beyond origin narratives. Understanding the molecular building blocks for intracellular organization informs cell biology and synthetic biology, where researchers aim to engineer compartmentalization. If fundamental elements of eukaryotic architecture have deep prokaryotic roots, those elements may be more modular and evolvable than once thought.

Ecologically, the presence of transitional forms in both marine and terrestrial sediments implies the evolutionary stage was not confined to one niche. This widens models for where and under what environmental regimes complex cells could have emerged, including settings with fluctuating oxygen that would favor metabolic partnerships.

However, important uncertainties remain: timing of specific events, the selective pressures that favored endosymbiosis, and whether the host‑like features observed were sufficient for full engulfment or required additional innovations. Resolving those questions will require better fossil proxies, more complete genomes, and experimental systems that recapitulate key steps in cell complexity.

Comparison & Data

| Feature | Prokaryotes (archaea/bacteria) | Eukaryotes | Transitional taxa (examples) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated origin | >4.0 billion years ago | 2.5–2.0 billion years ago | — |

| Membrane compartments | Generally absent | Nucleus, organelles | Membrane remodeling, invaginations |

| Cytoskeleton | Minimal/filament proteins | Complex filament networks | Primitive filaments, actin‑like proteins |

| Mitochondria | Absent | Present (endosymbiotic origin) | Host candidates with trafficking genes |

The table summarizes key distinctions and where newly characterized archaea fall between categories. While prokaryotes dominated early Earth, the genetic and structural complexity observed in some archaeal lineages suggest a graded, not abrupt, transition toward eukaryotic organization. Quantitative genomic comparisons in the cited studies show conserved gene families associated with membrane dynamics and cytoskeletal elements across multiple archaeal clades.

Reactions & Quotes

Scientists and commentators responded to the new syntheses by noting both excitement and caution. Reporters highlighted the visual footage and genomic data as complementary lines of evidence, while specialists emphasized the need for functional validation.

Researchers described the imaged cells as showing intermediate structural features that link archaeal lineages to early eukaryotes.

The New York Times (news report)

Independent experts quoted in coverage warned that morphological resemblance does not alone prove direct ancestry; functional experiments are needed to test whether the observed components behave like their eukaryotic counterparts.

Coverage noted that gene presence and cell architecture together strengthen—but do not finalize—the case for archaeal intermediates in eukaryote origins.

The New York Times (news report)

Unconfirmed

- No direct experimental demonstration yet shows that the filament‑like structures in Lokiarchaeum function identically to eukaryotic cytoskeletal systems.

- The precise timing and sequence of events that led from archaeal host to fully compartmentalized eukaryote remain unresolved and require additional dating evidence.

- It is not yet proven that the lineages sampled represent the actual ancestral host of mitochondria rather than close relatives that evolved similar features independently.

Bottom Line

The convergence of high‑resolution imaging and genomic data has substantially narrowed the conceptual gap between simple prokaryotes and complex eukaryotes by revealing archaeal lineages with intermediate features. These discoveries make it increasingly plausible that components of eukaryotic cell organization evolved in stages within prokaryotic relatives, rather than appearing abruptly as a single innovation.

Still, key questions persist about function, timing and ecological context. Future work that couples laboratory experiments, broader environmental sampling and improved molecular clocks will be essential to move from plausible scenario to detailed narrative. For readers, the takeaway is that the origin of complex cells is becoming a testable, data‑rich field rather than an intractable historical mystery.

Sources

- The New York Times: How Microbes Got Their Crawl — news report (The New York Times).