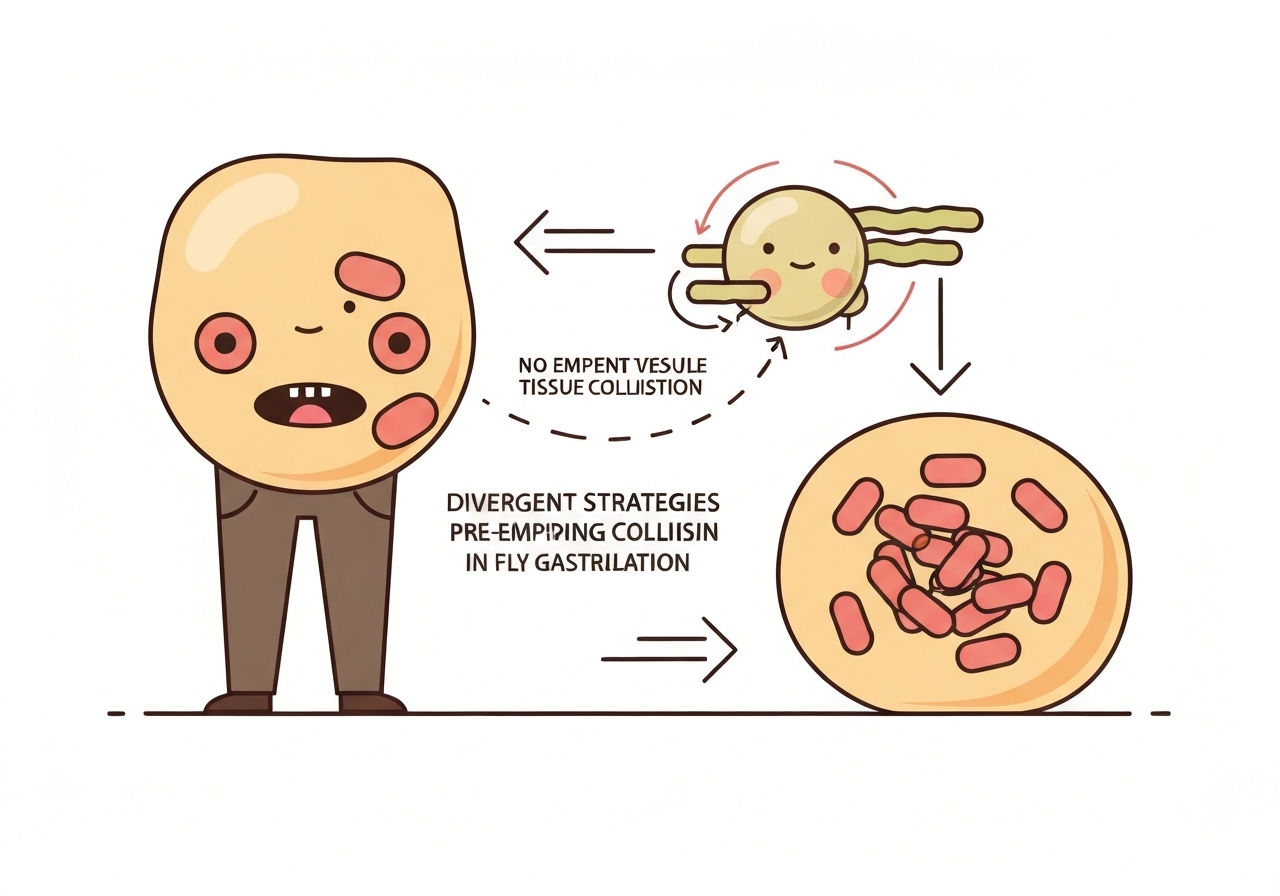

Lead: A comparative study across dipteran embryos shows that two distinct, evolved mechanisms prevent destructive head–trunk tissue collision during gastrulation: Cyclorrhapha (including Drosophila melanogaster) form a transient cephalic furrow (CF) that acts as a mechanical sink, while non-cyclorrhaphan species such as Chironomus riparius instead use out‑of‑plane cell divisions to limit head expansion. Loss or removal of the CF produces compressive stress, tissue buckling and later head and ventral nerve cord (VNC) defects.

Key takeaways

- The cephalic furrow (CF) is present in Cyclorrhapha but absent in surveyed non-cyclorrhaphan flies (for example, C. riparius).

- In D. melanogaster the CF forms near ~33% embryo length, persists ~90 minutes, and incorporates flanking head and trunk cells.

- Genetic removal (eve1 KO, btd mutants) or local optogenetic inhibition of CF formation causes delayed, passive head–trunk buckling driven by accumulated compressive stress.

- Non-cyclorrhaphan heads (C. riparius and others) show out‑of‑plane mitoses in specific mitotic domains that reduce apical surface expansion and shorten expansion duration.

- Re-orienting mitoses in Drosophila (Insc overexpression) reduces domain expansion and partially suppresses buckling, demonstrating functional interchangeability of the two strategies.

- Blocking mitosis (stg mutants) or ablating germband extension (khft mutants) lowers buckling, implicating head mitosis and trunk convergent‑extension as sources of collision stress.

- Acute CF loss via optogenetics increases the frequency of midline distortion and later head involution and VNC condensation defects, indicating developmental costs when the mechanical sink is absent.

Verified facts

Comparative phylogenetic and imaging surveys across Diptera show the CF is a synapomorphy of Cyclorrhapha. In D. melanogaster the CF emerges roughly at 33% embryo length at gastrulation onset, invaginates and remains as a transient epithelial fold for about 90 minutes before retracting; flanking head and trunk cells flow into the fold and become part of it.

Functional tests establish the CF as a genetically patterned mechanical sink. Targeted loss of eve1 (eve1 KO), canonical btd or eve mutants, or local optogenetic inhibition of actomyosin contractility in the presumptive CF region abolish CF formation and lead to a characteristic head–trunk buckling event. This buckling typically occurs several minutes after PMG invagination (reported mean delay ≈ 9.4 min relative to PMG invagination) and lacks the planar‑polarized Myosin‑II signature and gradual cell shortening that mark active CF formation, indicating a passive instability triggered by compressive stress accumulation.

Mechanical provenance of the stress was probed by perturbing head or trunk expansion. Eliminating mitotic rounds with stg (string/Cdc25) reduces or prevents buckling when CF formation is blocked, showing that head mitoses contribute to posterior‑wards head expansion and compressive load. Similarly, abrogating germband extension (khft quadruple mutants) removes the anterior–posterior divergent flows from the trunk and suppresses buckling, implicating convergent‑extension forces in collision generation.

In contrast to Cyclorrhapha, multiple non‑cyclorrhaphan species (Hermetia illucens, Coboldia fuscipes, C. riparius, C. albipunctata) show a double layer of nuclei in the head ectoderm during early gastrulation produced by out‑of‑plane cytokinesis. In C. riparius roughly half of the MD2 cells divide out‑of‑plane in a distinct anterior subdomain (MD2o). Out‑of‑plane divisions expand apical area less (≈1.6× for a shorter period) than in‑plane divisions (≈1.9–2× for ~24 min), reducing net surface demand and the duration of expansive stress at tissue scale.

Context & impact

These results argue that embryonic tissues evolve distinct mechanical strategies to avoid harmful inter‑tissue collisions when morphogenetic events run concurrently in a confined geometry. The CF acts as a transient, actively generated tissue sink that absorbs converging flows from head and trunk, while out‑of‑plane mitoses reduce the magnitude and duration of head expansion and thereby act as a passive stress‑dissipation mechanism.

From an evolutionary perspective, mapping these traits suggests the CF arose in the cyclorrhaphan stem group alongside a shift toward widespread in‑plane head divisions. Whether in‑plane division preceded CF evolution or vice‑versa remains unresolved, but either sequence would create selective pressures for complementary mechanical solutions and may represent a case where morphogenesis and mechanics co‑shape evolutionary trajectories.

- Practical implication: transient epithelial folds can serve mechanical roles beyond tissue shaping, buffering flows to preserve developmental robustness.

- Conceptual implication: mechanical instabilities (buckling, wrinkle-to-fold transitions) can reveal latent conflicts between adjacent morphogenetic programs and drive the evolution of novel morphogenetic modules.

The authors frame the cephalic furrow as a genetically specified mechanical sink that pre‑emptively dissipates compressive stress at the head–trunk boundary.

Dey et al., Nature (2025)

Unconfirmed / open questions

- Which trait evolved first in the Cyclorrhapha lineage: the shift to widespread in‑plane division or the CF? Phylogenetic correlation is suggestive but not conclusive of causality.

- The fitness consequences of CF loss under natural environmental variation (temperature, developmental rate) remain unmeasured; laboratory phenotypes show increased incidence of late head and VNC defects but direct fitness assays are lacking.

- The precise genetic changes that rewired division orientation and CF initiation across lineages (beyond eve/btd expression overlap and insc distribution) require further molecular dissection.

Bottom line

Gastrulation in flies exposes a mechanical conflict between expanding head and trunk tissues that evolution resolves in two main ways: Cyclorrhapha deploy a transient cephalic furrow as an active mechanical sink, while several non‑cyclorrhaphan flies reduce surface expansion through out‑of‑plane divisions. Functional experiments show these strategies are at least partly interchangeable and that removing the CF in Drosophila produces measurable developmental defects, underscoring the biological importance of mechanical stress management during early development.