Lead

On Valentine’s Day (Feb. 14, 2026), psychiatrist and neuroscientist Dr. Yoram Yovell spoke with Dr. Sanjay Gupta on the Chasing Life podcast about how romantic breakup, fading friendships or bereavement can change the body as well as the mind. Drawing on neuroimaging, clinical observation and a 2016 clinical trial he led, Yovell outlines five biological pathways through which loss manifests and offers practical steps people can take to begin recovering. He stresses that acute mental pain has evolutionary purpose but that chronic, disabling anguish deserves medical attention. The conversation emphasizes reconnecting with others, using safe behavioral tools like exercise, and targeted treatments when needed.

Key Takeaways

- Heartbreak is common: research indicates more than 80% of people experience a broken heart from a romantic split at some point in life.

- Brain overlap with physical pain: fMRI studies show brain regions activated by physical pain also light up during emotional pain, explaining why grief can feel physically crushing.

- Attachment and the brain’s “loss” system: separation activates circuits tied to infant–caregiver bonds and can trigger sadness, anxiety and depressive responses.

- Natural buffers: social contact and physical activity release endorphins that reduce both emotional and physical pain.

- Medical interventions exist: over-the-counter analgesics can slightly blunt emotional pain in mild cases; in 2016, very low-dose buprenorphine reduced severe mental pain and suicidal thoughts in a controlled trial led by Yovell, though long-term opioid use is not recommended.

- Rare cardiac risk: severe emotional stress can precipitate takotsubo cardiomyopathy, a temporary heart condition resembling a heart attack.

Background

Heartbreak is nearly universal and can arise from many losses: romantic breakups, friendships that fade, or the death of someone close. Evolutionary theories propose that the distress we call heartbreak evolved to maintain crucial social bonds—separations threatened survival in ancestral environments, so the brain developed mechanisms that push us to repair connections. Clinically, the intensity and duration of mental pain vary widely: most people recover with time and social support, while a minority develop prolonged grief or depression that impairs functioning.

Research in social neuroscience has traced these feelings to specific neural networks. Neuroimaging shows overlap between areas that process physical nociception and those engaged by social rejection or loneliness; this neurobiological convergence helps explain visceral symptoms such as chest tightness, stomach disturbances and sleep disruption. Health systems and clinicians increasingly recognize that severe, persistent emotional pain may require formal assessment and, in some cases, medical or psychiatric treatment similar to how chronic physical pain is managed.

Main Event

On the Chasing Life episode, Dr. Yovell described how heartbreak manifests across body and brain. He recounted personal experience—losing his father at 14—and linked that memory to the enduring physical sensation of loss. Clinically he notes that patients report a “crushing” chest and sleepless nights, symptoms that map onto known neural pain pathways.

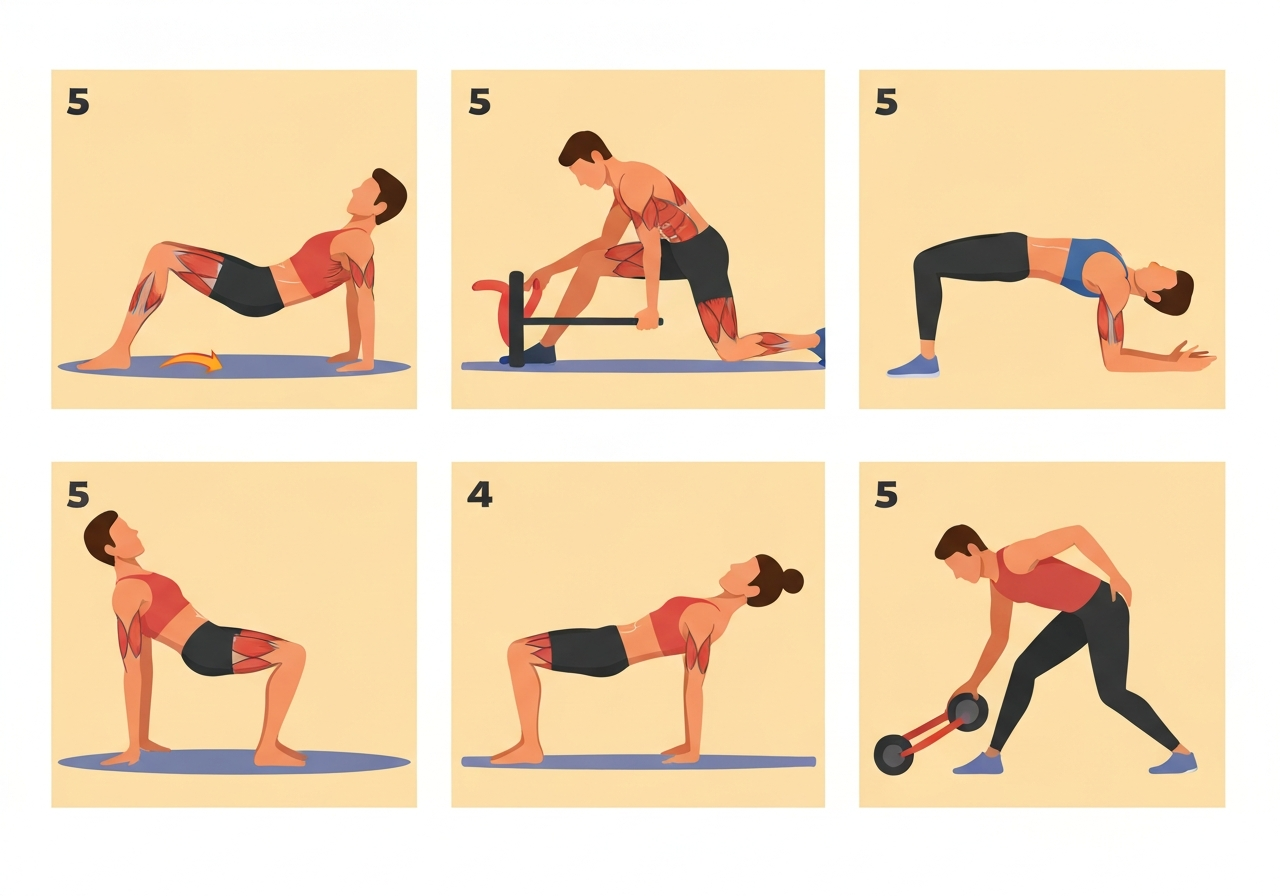

Yovell summarized five mechanisms the science highlights: (1) overlap of emotional and physical pain circuits; (2) activation of an evolutionary “loss” system tied to attachment; (3) endorphin-mediated natural relief from social contact and exercise; (4) partial symptom relief from nonprescription analgesics in mild cases; and (5) targeted opioid-pathway treatments (like very low-dose buprenorphine) for severe, short-term crises. He cautioned that opioid medications can relieve mental pain but are not a safe long-term fix.

He also emphasized the therapeutic power of social presence. Rather than isolating, people in a network should reach out to the hurting person—inviting them out, offering company and not withdrawing if initially rebuffed. Yovell framed this as both an immediate comfort and a biological intervention: social contact triggers endorphin release and dampens distress.

Analysis & Implications

The finding that emotional pain and physical pain share neural substrates reframes heartbreak from a purely psychological event to a biopsychosocial one. That framing has clinical implications: clinicians can validate visceral symptoms, screen for medical and psychiatric risk (including takotsubo cardiomyopathy and suicidal ideation), and offer a tiered response ranging from psychosocial support to evidence-based medication when indicated. Public health messaging should therefore normalize somatic grief reactions while directing those with severe or persistent symptoms to care.

Endorphin-mediated relief from social contact and exercise suggests low-cost, high-access interventions that health systems and communities can promote. Group programs, peer support, and safe encouragement of physical activity could be scaled as part of primary care and community mental health. However, relying solely on social strategies risks missing people whose neural or attachment vulnerabilities produce prolonged dysfunction; targeted clinical assessment remains essential.

The 2016 buprenorphine trial offers proof of concept that modulating opioid-related pathways can relieve acute, severe mental pain and reduce suicidal thoughts. Yet translating that research into routine care raises questions about selection criteria, dosing, monitoring and long-term consequences. Policymakers and clinicians must weigh benefits against addiction risk, regulatory constraints, and the moral imperative to treat intractable suffering humanely.

Comparison & Data

| Feature | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Prevalence of romantic heartache | >80% of people report a broken heart from a romantic split (research cited by experts) |

| Neural overlap | fMRI studies show physical-pain regions activate during social rejection |

| Intervention effects | Endorphins (social contact, exercise) provide nonpharmacologic relief; very-low-dose buprenorphine reduced severe mental pain in a 2016 trial |

These comparisons place common, low-risk interventions (social support, exercise) against select medical options for severe pain. The table summarizes where evidence is strongest (neuroimaging, population prevalence) and where clinical trials exist but require cautious interpretation (opioid-pathway medications).

Reactions & Quotes

“Mental pain is the high price we pay for our capacity to love; it evolved to protect bonds,”

Dr. Yoram Yovell, psychiatrist and neuroscientist

Yovell used his clinical and personal experience to argue both for the value of acute distress as a signal and for active support when pain becomes disabling.

“Presence matters — a caring person can trigger biological systems that reduce pain,”

Dr. Sanjay Gupta, CNN Chief Medical Correspondent

Gupta framed social contact as a measurable, biologically plausible way to relieve distress and urged listeners to offer support rather than withdraw.

Unconfirmed

- The precise population-level rate at which takotsubo cardiomyopathy follows emotional heartbreak is not established and is considered rare.

- The degree to which over-the-counter analgesics reliably relieve emotional pain across diverse populations requires further replication.

- Long-term safety and optimal protocols for using opioid-pathway medications to treat chronic mental pain remain under study and are not standard practice.

Bottom Line

Heartbreak commonly produces real, measurable bodily effects because the brain processes emotional and physical pain in overlapping systems. Most people improve with time, social reconnection and self-care measures such as exercise, which stimulate endogenous endorphins. For a minority with severe, persistent suffering—marked by suicidal thinking, incapacitating depression, or physical complications—clinical assessment and targeted treatments may be necessary.

If you or someone you know is in immediate crisis, seek help: in the U.S. call or text 988 for the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. Globally, local crisis centers can be found via the International Association for Suicide Prevention and Befrienders Worldwide. Reaching out, staying present for others and combining psychosocial strategies with professional care when needed offers the clearest path from acute pain toward healing.

Sources

- CNN — Chasing Life with Dr. Sanjay Gupta (news interview, Feb. 14, 2026)

- Hadassah Medical Center / Hebrew University (academic/clinical affiliation for Dr. Yoram Yovell)

- International Association for Suicide Prevention (global crisis resource, nonprofit)

- Befrienders Worldwide (global crisis resource, nonprofit)